Last updated on December 29th, 2023 at 01:44 pm

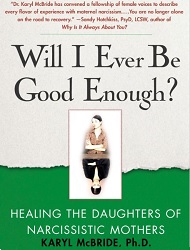

I promised readers that I would post my completed Daughters of Toxic Mother research questionnaire. I figured so many women have already trusted their stories with me; why not share my answers to the interview questions I ask the daughters of toxic mothers?

Really, how hard could it be?

I designed my research questionnaire rather quickly, figuring it would take most survivors an hour or two to complete. When I receive the answers to the survey, I am often astounded by the honesty, the heart, and the sheer bravery of some submissions. The time has come for me to put up or shut up. This extra-personal article proves it wasn’t as easy as I thought.

Who knew I would have to consult friends and family about what to include and how to say things?

Who knew I would lose sleep or take ALL DAY to write it and then hit publish? I have struggled with the concept of privacy versus helping others. In the end, I self-edited a bit and decided to save some hard-to-tell bits for the book—after all, more than just my initials.

While I had quoted other daughters of toxic mothers in past columns, they had been identified only by initials and birth year. Through my survivor’s submissions, I learned that getting to the nitty-gritty requires some protection and anonymity. Rest assured, I documented many embarrassing stories in this post, which runs about five times longer than a standard post.

Daughters of Toxic Mothers Questionaire

1. Tell us about you. What year were you born, and where does your birth fit in among siblings? Please provide a basic description of your parents/family. Did your family grow through adoption or foster placement?

I was born in the 1950s in San Francisco to a teen birth mom from Iowa who put me up for adoption. My adoptive parents had adopted my brother five years earlier. I was told that I was their chosen child, the child they waited five long years for. At the time my father, who worked with his twin brother at their father’s print shop, didn’t make enough money to qualify for a social services adoption.

My price tag was $2,500, upfront. I later learned that during the waiting period my grandfather would cut false paychecks for my dad to show social services to qualify for the adoption process.

My dad would return those checks to my granddad so they could be ripped up. Where there’s a will, there’s a way, I guess.

My mother was a beautiful girl from Farmington, Utah, raised by good modern Mormons. Her father was a railroad conductor (sweet and funny, but away a lot) and her mother was an alcoholic floozy from a hardcore polygamous clan. My mother told us she ran away from Utah, but I later discovered that she had actually been kidnapped by her mother who brought her to San Francisco to lead a life of debauchery. I know my mother suffered.

My father was raised in San Francisco during the Depression by a stern, domineering German-American father and a gorgeous, lovely, but quiet mother. When they were eight years old, their father “parked” them in an orphanage while he looked for work. The “boys” worked for my grandfather all of their lives.

A defining incident of my dad’s young life was a terrible accident at the shop.

My brother and I grew up in the print shop: me playing in a barrel of punch holes and making paper doll furniture; my brother riding his Schwinn around the cavernous warehouse and raiding the Coke machine. My father was a very talented artist and cartoonist at a young age.

People have no idea how dangerous print shops of that era were. All the cutting and chopping, the hot glue, etc… One day a narrow, but long, circular saw snapped and began whipping in arcs and instinctively my father grabbed for it, chopping four of his fingers off. The ink poisoned the exposed flesh and microsurgery was not commonly available. Indeed, they went to two emergency rooms when the first doctor proceeded to make plans to cut off my dad’s entire hand.

The fingers were thrown away by the second hospital; each stub was clamped shut and for the rest of his life my dad had four very stubby stubs on one hand. Strangely enough, the fingernails continued to grow but they grew out from the center of each tip looking exactly like black dog nails. I loved my father’s injured hand, for some odd reason.

They say a character is defined by how you react to life’s setbacks. My father’s recuperation included considerable bed rest. He asked his mother to get him a roll of paper.

A BIG one.

She went to a butcher shop and bought a roll of coarse brown wrapping paper. My father filled the entire thing re-training himself to draw with his left hand. We have a section of dogs he did left-handed framed in my office.

He was happy to draw and do creative things with his hands all of his life. He also taught himself magic tricks to regain some fluidity in his hand. Many friends didn’t notice his loss for years and were startled to learn of his accident as a teen. He never lost a round of which hand is it in?

He could palm anything from dice to a champagne cork.

My mother’s early life was overshadowed by her mother’s immoral life. A red wine alcoholic she often traveled with her own brother registering at hotels as a married couple. When my mother met my dad she was a high school drop-out, working downtown and spending all her free time at the movies to avoid her mother.

On my parents wedding day she spent the morning checking her mother into a sanitarium and the afternoon celebrating her nuptials.

2. Describe the arc of your academic and professional life to the present. What is your current occupation? If you volunteer in your community, how often? Doing what?

I attended a private Catholic girls’ high school because my mother decided it was the best private school in the San Francisco because it was right across the street and there were NO boys. I was neither Catholic nor happy as a teen at school. My parents had divorced and my mother was dragging my brother and me through her horrible second marriage to an alcoholic wife-beater and verbal abuser.

We lived in a 14-room home, yes, but it was a hell-house for my brother and me. The environment was so volatile neither one of us ever invited anyone over. Indeed, my first serious boyfriend was a 22-year-old San Francisco cop who had been called to the house during a night of domestic violence involving a butcher knife rampage.

I was age 16 when we began dating and he became my knight — always available to sweep me up and protect me. My mother once threatened to report him to his bosses and he said, “Please do that so I can tell my bosses about you and your husband.” I loved that guy.

Because of the many sleepless nights, the stress of my home environment, I went from being a rather good student in public middle school to a failing ghost at my new high school.

I skipped classes most of the time, preferring to lie on the school library carpeted floor, reading away my days. (When I was younger I regularly carried adult books about trying to impress my teachers.) In my junior year, my mother gave me a red set of American Tourister luggage for Christmas, explaining that I’d have to get going, get on with my life when I turned age 18. I had no idea what to do or where to go.

It’s hard to believe in our current environment of parental micromanagement of the road to college, there was never any discussion of college. My school counselor, after spending about 10 minutes with me, suggested I’d be happiest working in retail.

My first job was as a file clerk at the Pacific Stock Exchange.

Remember the last scene in the movie, Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark? The huge warehouse with all the crates marked Top Secret as far as the eye could see? The stock exchange had filing rooms kind of like that with filing cabinets taller than me. I was so happy working — alphabetizing. I shared an apartment with a girlfriend and paid my bills, dated, and I was super happy on my own. My boss said he could always find me by listening for me singing Patsy Cline songs.

The stock exchange is where I learned the value of working hard in a meritocracy. I kept my head down and worked my way up to a position of trust, a listing representative in the marketing department at the exchange.

Later, I took jobs at brokerage houses and was usually the youngest and often the first girl to work in many trading rooms on Montgomery Street. During this time I inquired about college, I took a few courses at City College, UC extension (earning all A’s) but never had the focus or the resources to really apply myself.

When a Vice President of the stock exchange was recruited to be a headhunting partner, he recruited me to be his research assistant. That was one of the most amazing miracles of my life.

Someone actually recognized that I had a brain. I spent a dozen years in global, high-ranking executive search, eventually become director of research for a boutique firm. I interviewed thousands of business leaders, developing perspective on what makes people good hires — mainly a decent brain and good character.

Identifying a skill I didn’t realize, I possessed my boss encouraged me to become a freelance writer and paid for all my early writing courses. He became a second father to me, encouraging me always. I had amazing success selling everything I wrote.

I parlayed freelancing into my own self-syndicated business column in several major newspapers sharing what I’d learned in recruiting. That led to my first reporting job with a New York Times regional newspaper, where I spent a decade writing the first draft of history for my community.

I have been a business columnist for the S.F. Chronicle/Examiner and Seattle Times, a business reporter, a community reporter covering philanthropy and volunteering at a daily paper, as well as a top blogger for the newspaper I left to commence this book project.

I’ve taught writing and become a decent public speaker after spending most of my life grateful for jobs because I thought I was kind of dumb. I have always been a voracious reader, a self-educated autodidact. In a way, my life has been my education. I do volunteer in my community as a law enforcement chaplain, helping the police deliver death notifications. It’s a terribly hard task requiring significant training. When I was a reporter I covered volunteering and I felt that my stories went a long way to marshaling community support.

I was a key contributor (via my reporting) to raising several million dollars to build a new children’s home, for example. I specifically chose stories that I thought would do the most good.

Personally, I support my local animal shelter and a non-profit book-mobile. I also bless every driver who uses his or her turn signals.

3. Describe the relationship with your mother in three segments: as a child, a teen, and a young adult.

My mother (meaning my adoptive mother who raised me) was beautiful, wore furs if she could, red lipstick, Joy perfume and hypnotized me visually when I was a child. She was warm and soft and I enjoyed nothing more than sitting in her lap with her silk-lined camel coat wrapped around us, snug. I enjoyed a long period of just adoring my mother, up until I was about age 5 or 6.

By age eight my parent’s marriage was on the rocks because of my mother’s constant shopping for a (new) rich husband, aggravated by my father’s increased drinking. They fought a lot in our small flat. I was left in my brother’s care most of the time. I began to see that my mother had mostly “not nice” days. Like kids of that era, we spend every waking moment outdoors. But that wasn’t enough for my mother. She would lock us out of the house to sleep — I realize now it was because of drinking and depression — but at the time I thought she didn’t love us anymore.

I had to shake her awake and beg her to feed us, which she would do reluctantly making us Cream of Wheat for dinner or tossing us a slice of baloney for breakfast, whatever was handy. We’d have to show her that our hands were shaking before she’d feed us. She began punishing us by breaking wooden spoons on our legs, then slapping us when she couldn’t find more wooden spoons. She was unpredictable . My brother and I suffered in silence.

It amazes me that neither of us ever complained to our father, relatives or neighbors. It was like we didn’t want to rat her out. She also did this thing we called “flipping” our lips. My mother was maniacal about buffing and polishing her nails, which were perfectly formed ovals like Jordan almonds. To this day I can’t use “her” colors — pale mauves, peaches and rusts — on my nails.

Imagine there’s a crumb on the table. It’s a big crumb and you plan to flip it with just the tip of your middle finger to send it flying as far as it can possibly go. You put a lot of force, a bit of snap as the finger exits the thumb.

That’s what my mother would do to our lips with her big, shiny nails. Sometimes we’d move defensively and she’d catch our noses, which hurt more. My mother’s second marriage was violent from Day One but it began truly breaking down when I was in high school. She found a way to blame me.

After all, if I had been nicer, he would have stayed. This was my mothers twisted way of weaving our misfortunes into her misfortunes.

My mother started to complain that I walked around the house too much and looked trampy. (I was a 32D by sophomore year.) She refused to buy me any clothes other than my school uniform. Any clothes I had for play were my older brother’s old jeans or t-shirts, which I tailored down by hand.

My grandmother (my father’s mother) eventually took me shopping for brassieres — a true kindness on her part. She took me to the City of Paris annually for bra shopping. It was she who paid for made to order bras for me until I left home. Our demi-mansion had an upstairs suite: two large bedrooms with a connected bathroom. By high school my brother and I each stayed in our rooms with the doors locked most of the time. If one went downstairs for any reason, we’d ask the other if he or she needed anything.

It was like a war. “I’m going down…” we’d say to each other, knowingly. “Want crackers?”

I left home, more or less, by 17. Before that I had been a chronic runaway. And yet, as a young woman I wanted to spend time with my mother. By then she was divorced and living in a sad, small condo about an hour away by train. I lived with a bunch of girls in an apartment and some weekends I just wanted a break from them, so I’d take the train to my mothers and we’d spend all weekend watching movies.

Somewhere around age 25, I began to realize that my mother was a little crazy, a little too weird. I got the idea that each time I saw her it was like I was exposing myself to a virus. I’d see her and feel terrible for days. At that time I lived in an apartment complex on the California Street cable car line.

It had four pods of apartments around a large rectangular pool situated on the better part of a city block. There were two entrances (on two opposite streets) both with heavy iron bars facing the streets and locked gates. People had to be buzzed in.

When taking out garbage via an alleyway, one could see out to the street through the main fence without being seen. One night while taking out the garbage I was startled to see my mother there on the sidewalk with her back to the fence. She was crying into a hankie just outside my gate.

I stood frozen.

I expected to snap out of my shock and go to her but I just stood there holding my breath. I was afraid of her like I’ve never been afraid of anybody. I was Bambi coming up behind the hunter. It didn’t matter to me what her drama was: who hurt her, beat her or rejected her.

I think that was the moment of my initial adult emotional separation from my mother. That’s when instinct overtook my emotional desire to have a mother; any mother. I backed up, holding my garbage to my chest. With my hand firmly flat against the door, I kept it from slamming or even clicking shut.

4. How old were you when you first realized your mother was different than other mothers?

Because I grew up in a city, in a neighborhood where all the kids knew each other’s homes as well as their own, by age 8 or 9 I knew my mom was different. I felt that she was more concerned with her own life than being a mother. I knew she was out for herself.

5. What is your biggest criticism of your mother?

As an adult I see that some of her damage, she couldn’t help. But my main criticism of her is still that she was unnecessarily cruel.

6. What would she criticize about you?

When I cried she used to say, “Poor Rayne, you’ve got it so rough!” I know now that from her perspective my life was so much better — practically Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm — compared to her childhood.

She felt I had no reason to complain about anything.

7. Describe any significant periods of estrangement. How easy (or difficult) was it to limit (or cut off) contact?

Beginning in my mid-20’s I would avoid my mother for weeks or months at a time. When we did have contact she would know the exact date of our last conversation and remind me of it.

It made me feel guilty and I’d try to check in more often to avoid it. But each time she’d pull the same thing so I figured I’d get the same verbal slap in the face whether I went a week or summer, so the periods of no contact got longer and longer. When I was age 26 my mother crashed my first wedding, got drunk and made a fool of herself. She had to be carried out of the dining room by staff of the Awanhee Hotel in Yosemite. It didn’t embarrass me at all.

By then I had really separated her life and my life. The morning after the wedding I found a wrapped box on the hood of my car. It was a photo album from my childhood. That was her weird wedding present to me — documentation of my great childhood.

The happier I was the easier it was to have no contact. My second husband never met my mother. She died unexpectedly in 2009. I have no doubt that in the end my mother didn’t want to see me because she didn’t want to be seen as old and frail; gray and wrinkled, pulling a small oxygen tank behind her.

In the last two years of her life I spoke to her a handful of times. She initiated the calls. When I told her we hadn’t spoken for most of two decades, she asked why.

“Because you were not a very nice mother,” I said.

“Reeeeeeeealllllly?” she squeaked.

I didn’t believe that she had forgotten all of her many sins against us. I distinctly remember thinking: That’s interesting. She’s trying to see if I’ll believe that she is so old she’s forgotten.

8. How has your relationship with your mother affected your relationships with others?

I didn’t realize how much until recently. I was a gregarious loner because I didn’t trust people not to turn on me. I said I preferred men friends to women friends in general, but in truth, I feared any woman who had any similar trait to my mother. I missed out on a lot of friendships because of it. I tended to take a lot of bad treatment and suffer in silence.

That’s how I had coped since I was a kid.

9. How many friends can you really talk to about your mother?

I always tell the truth about my mother if it comes up. I can tell anyone anything they want to know.

10. Describe your current family status. Do you have children? If not, why not?

I have been happily married for 14 years to an awesome man. I have no children. Neither of us does but we are the cool aunt and uncle to several children in our social circle.

Like a lot of daughters of toxic mothers, I consciously chose not to make babies thinking that I might let them down or hurt them. We dote on our dogs and enjoy theater, music, and travel. We entertain a lot. We laugh a lot.

11. Describe your current relationship with your mother. Given your current levels of contact, how are you viewed within your family?

My adoptive mother is deceased. I’m writing about her with family support. My birth mother is alive and wants no contact with me. I’m her mistake. Her secret. My step-mother (my father’s widow) lives 20 minutes away and we love her and look out for her. She’s a great lady.

12. Have you ever talked to a therapist about your mother? Was it helpful?

What is amazing to me is that I never thought I needed to or could benefit from therapy. My father always feared therapists. He’d say if you feel like your head is scrambled go hug a tree; get out in nature.

It wasn’t until I was severely stressed out at work and sought therapy that I learned that I could handle plenty of stress until some personal exchange triggered my mother’s voice in my head belittling me. That voice could irrationally convince me I’d be fired; when it wasn’t the case. Work stress could quickly morph into childlike fear of my mother coming at me, although I didn’t really connect the dots without a therapist’s help.

With therapy I was able to unearth and face long-buried incidents. For example, there is a technique where the therapist has you hold your head still and you follow their finger or an object to the left and to the right with your eyes while describing a person or incident from your life.

The idea is that you are re-thinking experiences using both your left and right brains, basically.

During that session I recalled my mother flipping my lip, knocking my head back and making me cry. Literally, I felt it in my therapist’s office and reacted as if my mother was in the room. It startled my therapist, I think. I had forgotten that regular form of humiliating punishment. I later called my brother to make sure my memory was authentic and he confirmed that we both were regularly “flipped” in the face by our mother.

I had a very good therapist who gently lifted heavy weights off my shoulders. She helped me sort out fresh normal stress from old buried stress. She taught me to recognize when it kicks in and the difference between my own subconscious voice and my mother’s voice on boxed wine.

You know the one who says, who do you think you are, smartypants? I wish I had gone earlier.

13. Moving forward, do you anticipate any changes in your view of your mother?

If I were writing fiction based on my mother, this would be much easier because the story would stay the same. I realize that no matter how much I bare my soul for this book, in the future my perception of my life might change a little as I continue to mature.

Hard to imagine now but I may be more forgiving at some point.

I have been doing family history work on my mother’s family and most everything I learn increases my understanding of her life. So changes in my view of my mother are inevitable. She came from a fundamental Mormon family with lots of polygamy and old man/young girl stuff. Remember the President of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, Warren Jeffs? The man who liked 14-year-old brides?

Same family.

She also was kidnapped by her mother (this is something I know about my mother that she herself did not know) who dragged her along on her own alcoholic and man binges. No doubt my mother had a hard life. But a lot of women do and they still manage to treat their children with respect.

14. Do you experience personal guilt, social guilt, or remorse about the decisions you’ve made regarding your mother?

Not at all. My only regret is that I was not firmer about the early breaks. I wasted a lot of energy and emotion giving her chances to be a mother. The child in me always wanted a mother. Today I am my own mother in a weird way.

I try to be kind to myself and to take care of myself. And I’m not afraid to let others mother me. I can accept kindness and concern in a healthy way now. I’ve even learned to ask for help, something I wasn’t able to do for over 40 years. When I ask my husband for help, he thanks me for giving him the opportunity to be supportive.

He knows it’s that hard for me.

15. As your mother ages, do you see yourself having more or less contact? Why?

I never had plans to be there for my mother. My brother and I agreed that we would make phone calls or sign things for her as needed to make her life easier, but neither of us would be driving her to appointments or checking on her physically. That was the right decision.

In 2009 my mother checked herself into a hospital for pneumonia and died two days later. It was very unexpected. A former smoker, she had COPD — trouble breathing — and used oxygen, so even a cold could have killed her, we were told.

The first day she went in her friend called my brother and he called me. We discussed whether one of us or both should travel to the hospital. But why, we debated. It wasn’t like we could do anything positive for her. Plus we ran the risk of her saying or doing something that might haunt us.

My brother (the big softie) was leaning towards going but was really dreading it. At first I said I absolutely wouldn’t go, but then said if he went I would, too. I didn’t want him going by himself. Together we were stronger. Together we could make any of her outbursts comical.

We agreed to sleep on it and I was resigned to going for him even going so far as planning time off from work.

That morning I was out on a story. I was a newspaper reporter and my brother called me just before I got out of my car to cover a small town fundraiser. It was a quaint event put on my ladies who donated knick-knacks, honey, jams that sort of thing for sale to raise money for some little non-profit.

It was a sunny day and I had parked on a dirt road under a shady tree. My phone rang. My brother said our mother had died the night before. I rolled down my window and listened to bees buzzing nearby. Within minutes we had agreed that because he lived closer to her condo and had more freedom (he’s not on the clock as I was on my job) that he would be the executor for the probate courts. My logic: every time we divided Halloween candy he always gave me my favorites and gave me extras.

I knew I could trust my brother.

After we hung up I sat there for a minute having that I’m nobody’s kid anymore feeling wash over me. But then I snapped out of it and went to work. The probate judge determined she died without a will and designated my brother as the executor with my sign-off. The probate took over a year. My brother worked his butt off, not only straightening out all her banking, investment and tax issues, but he also cleaned out and sold her condo.

On the day my brother visited me to write us each final checks granting us 50% of my mother’s small estate I expected to be ecstatic.

I imagined I’d be jumping up and down and kissing that check. I had been working since age 17. When had I ever received a big bag of money? As my brother drove away all I could think was: It is sad that she didn’t want either of us to get a dime.

I told my husband what I felt and he said “Think of it this way. You got a dime for every time she hurt you. Today was your payday. Be happy — you earned it.”

Rayne Wolfe

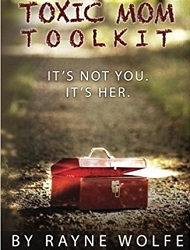

Even though Rayne Wolfe has now published her big dream book, Toxic Mom Toolkit, if you are a daughter of a toxic mother with a story to tell or feedback on how Rayne’s book helped you, we would be happy to publish your story on 8WomenDream. You can email us at dreamers(at)8WomenDream.com.

|  |  |  |

|---|

Rayne Wolfe is a versatile and accomplished writer, author, writing coach, and freelancer. Her notable work includes ‘Toxic Mom Toolkit,’ a memoir that not only shares her personal journey but also features mini-stories from women around the globe who, despite facing the challenges of a toxic mother, have grown into resilient adults. As a seasoned journalist, Rayne has served as a former business columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle/Examiner Sunday and the Seattle Times, showcasing her ability to distill complex topics into engaging narratives that resonate with diverse audiences.

Note: Articles by Rayne may contain affiliate links and may be compensated if you purchase after clicking on an affiliate link.