Last updated on January 23rd, 2019 at 10:40 am

Hello my Thankful Thursday dreamers!

This week, I am grateful for the strong women in this world who speak out to end violence against women. Considering the outcome of the recent Oscar Pistorius trial in my country, I want to use this week’s post on 8 Women Dream to bring attention to the subject of violence against women.

Today I want to share an article by writer, Ché Ramsden, who explores feminist issues surrounding the Pistorius trial, how these issues intersect and their implications in a South African context.

Reeva Steenkamp: justice?

On Valentine’s Day 2012, Reeva Steenkamp became one of three women a day who are killed by their partner or ex-partner in South Africa.

On 11 September 2014, her killer was found guilty of culpable homicide (manslaughter).

The judge found that his version – that he mistook Steenkamp for an intruder, and so feared for his and Steenkamp’s lives that he believed he was acting in lawful self-defence by firing four shots through a locked toilet door – was ‘reasonably, possibly true’.

And so Oscar Pistorius was officially found not guilty of murder.

Verdict

Of course, a not guilty verdict means very little. People Opposing Women Abuse highlight that, in the fraction of cases that make it to court, even fewer receive a conviction.

If the verdict in the trial of Reeva Steenkamp’s ‘reasonably, possibly’ mistaken killer sets, in the Tweeted words of South African novelist Margie Orford, ‘the bar for thinking, foresight and responsibility…remarkably low,’ it falls firmly within the already low standards set by cases of women killed in the ‘private’ realm of the home.

Rachel Jewkes of the South African Medical Research Council says the need for reliable third-party evidence makes this legal framework ‘incredibly disappointing for women.’ As she says, ‘the law doesn’t always deliver what ordinary people call justice.’

It is not clear what justice looks like for a woman whose life ended at the hands of her partner. It is difficult to imagine any scenario in which the prosecuting state – let alone the family of the victim – could ‘win’ a case, even when an appropriate conviction is secured.

Reeva Steenkamp, it seems from the relatively little media coverage which focuses on her rather than the man who shot her, had a bright future ahead of her – and as a human being her life had intrinsic worth.

Yet 21 women a week in South Africa, like Steenkamp, have their lives abruptly cut short by their partner or ex-partner: this is not just, and no legal judgement could make it so. A constitutional aim for a country free from sexism is shamefully blighted, bloodied, ignored by repeated incidents of violence against women.

Two women

‘Justice’ would be the constitution upheld: in a more just society violence against women would not exist.

Kopano Ratele, in ‘Apartheid, anti-apartheid and post-apartheid sexualities‘, shows that many South Africans continue to internalize the ‘identities, desires, fears and relationships that apartheid fathers sought to cultivate on this land.’

I have previously written on openDemocracy 50.50 about the intersection between patriarchy and apartheid, twin foes deeply embedded, which the New South Africa has not yet managed to uproot.

While the new constitution expresses a desire that non-sexism – and, with it, an end to gender-based violence – would appear with the aspirational Rainbow Nation, any expectation that this could be realised in isolation of the rest of the world would be naïve.

Global perspectives

Last Human Rights Day (9 December 2013) the Executive Director of UN Women, former Deputy President of South Africa Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, issued a reminder of the sheer number of women who experience gender-based violence – one sixth of the world’s population, in figures well over a billion women worldwide: ‘that is nothing short of a pandemic and a massive human rights violation.’

Coming as it did days after Nelson Mandela’s death, Mlambo-Ngcuka used the global icon’s stature to add to her reminder: that the violation of human rights affects everyone, not just the oppressed.

In my second article in this series, I argued that the trial surrounding Reeva Steenkamp’s killing cannot provide South Africa with any solutions to its social problems; the prevalence of violent, unhealthy masculinities needs to be addressed by society at large.

Regardless of whether Reeva Steenkamp can be officially called a victim of ‘intimate partner femicide’, even by the defence’s (successful) argument she is nonetheless a casualty of what can only be described as a particular brand of masculine violence in which she was being ‘protected’ by her male partner.

This patriarchal attitude towards women is intrinsically tied to gender-based violence.

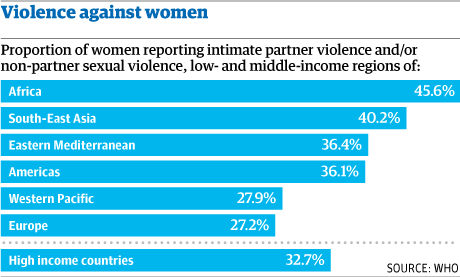

South Africa’s rate of gender-based violence is one of the worst in the world . However, the reality is that violence against women is a global phenomenon with appalling incidence everywhere.

In 2013 WHO, along with the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the Medical Research Council, analysed existing data from 80 countries and found that an alarming 35% of women experienced gender-based violence. 30% of women experienced physical and/or sexual violence at the hands of their partner and 38% of murders of women were committed by intimate partners.

These statistics do not take account of unreported incidence, nor of the damaging non-physical or non-sexual violence which many women experience.

We need to dig deeper to dismantle the culture(s) which make it acceptable to hate women.

Patriarchal culture

If the incomplete statistics are the mere surface of the pandemic, at its core rage two of the defining features of patriarchy – male privilege and male violence – as WHO explains : ‘the unequal position of women relative to men and the normative use of violence to resolve conflict are strongly associated with both intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence.’

Responses to violence against women indicate the worth ascribed to women in patriarchal society, and the inherent complicity of patriarchy with gender-based violence.

To give some recent high-profile examples: last week, footage emerged of US NFL star Ray Rice knocking his then girlfriend (now wife) Janay Palmer unconscious; prior to the release of the video and the outcry that followed, the NFL had given Rice a mere two-game ban for the incident.

In June the chief minister of Uttar Pradesh accused the media of ‘hyping up’ the rape and murder of two girls aged 12 and 14, while the Home Minister of Madhya Pradesh said, of rape, ‘sometimes it’s right.’

The recently-published inquiry into the sexual exploitation of at least 1,400 children in Rotherham, UK between 1997 and 2013 exposed the systematic way in which children were disbelieved and ignored by almost everyone with the power to help them. Some rapes were even deemed to be ‘consensual’, a legal impossibility for children – although British courts have not always upheld this law.

Towards justice

Violence against women is linked to women’s economic disempowerment; physically silencing women goes hand-in-hand with their exclusion from all public space. Whatever your position on the political spectrum, it is clear this happens at society’s peril.

On 12 September Christine Lagarde, Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund, appealed to Japanese politics and business for greater inclusion of women for the simple reason that it makes economic sense. By excluding women, ‘the global economy is not using its productive resources very effectively.’

As well as the economic benefits – which should allow states to increase social expenditure on progressive social policy – we also know that women’s education is directly linked to health outcomes, saving money in the long term. This is a concrete example of the way in which upholding women’s rights leads to enfranchisement for society as a whole.

South Africa does remarkably well on women’s inclusion in many public spheres, despite its record on gender-based violence.

42% of its parliamentarians are women and South African women like Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka also hold prominent international positions.

Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma who played an active part in the anti-apartheid struggle and was also a senior politician in South Africa, is now Chair of the African Union Commission – the first woman to hold this position.

On a local level, grassroots activism is also impressive; returning to Reeva Steenkamp’s death, the ANC Women’s League has remained strong in its support for Steenkamp’s mother, June, and protested outside court every day of the trial to alert the international media to the broader issues surrounding the case.

However, just as legal principles do not guarantee justice for women in the courts, nor principles of economic inclusion stop institutional and work-based discrimination, women having prominent positions in politics does not trump their cultural oppression.

As Chair of the African Union, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma was one of the dignitaries to address Mandela’s memorial service in December 2013. Her speech was impressive, and one of the best: honest, sincere and personal, placing Mandela in the context of Pan-African values and struggles for liberation.

Yet Dlamini-Zuma was ignored by the crowd to such an extent that the Master of Ceremonies had to interrupt several times to ask for silence, and most press cut away from her, unable to hear. While the crowd was vocal during most speeches, it was actively disrespectful of Dlamini-Zuma, the only woman to make an address.

This kind of patriarchal culture is not only reflected but unhealthily nourished by most of the media coverage of the trial for the killing of Reeva Steenkamp: coverage which has consistently erased Steenkamp (merely ‘the deceased’) in favor of Pistorius, unless it pauses to recognize her good looks and social status.

Silent women are objectified, masculinities privileged. Indeed, #YesAllWomen are affected by patriarchal aggression.

We need to recognise intersectionality in the oppression of women and the dismantling of patriarchy cannot be led by one particular site. A combination of economic policies, sound legal systems and social inclusion – with political and monetary investment in each – is necessary for a just society.

I ended my previous article in this series with a reference to the rallying cry which emerged from the 1956 march which heralded National Women’s Day: Wathint’Abafazi Wathint’imbokodo! In recent years this has transformed into the saying ‘you strike a woman, you strike a rock’, the subtext of which reads: ‘when you hit a rock, the rock does not break. But your action may dislodge a boulder which can crush and kill you.’

The apartheid laws women were protesting in 1956 are a good reminder that legal frameworks do not always provide justice for the oppressed – and no court judgement today, important as they are, can provide adequate justice for a woman killed.

The boulder which has been dislodged continues to gather momentum, and it will be good for women, men and children worldwide for patriarchy to be crushed.

—

Ché Ramsden works for a national children’s charity in the UK. She has previously been a Research Assistant at the London School of Economics (LSE) and has worked in voluntary positions with various organisations including UNICEF UK, for which she was a Youth Adviser, and Student Stop AIDS. She has an MSc in Social Policy and Planning from the LSE.

Ché Ramsden works for a national children’s charity in the UK. She has previously been a Research Assistant at the London School of Economics (LSE) and has worked in voluntary positions with various organisations including UNICEF UK, for which she was a Youth Adviser, and Student Stop AIDS. She has an MSc in Social Policy and Planning from the LSE.

This story was originally published on openDemocracy.

Thank you for reading,

Sue

[fbcomments]

Sue Levy is the founder of the South African Just Pursue It Blog and Inspirational Women Initiative. She’s a motivational writer and media designer, who is obsessed with everything inspirational with a hint of geek. She thrives on teaching women how to be brave and take big chances on themselves. You can find Sue on her Twitter page @Sue_Levy.

Note: Articles by Sue may contain affiliate links and may be compensated if you make a purchase after clicking on an affiliate link.